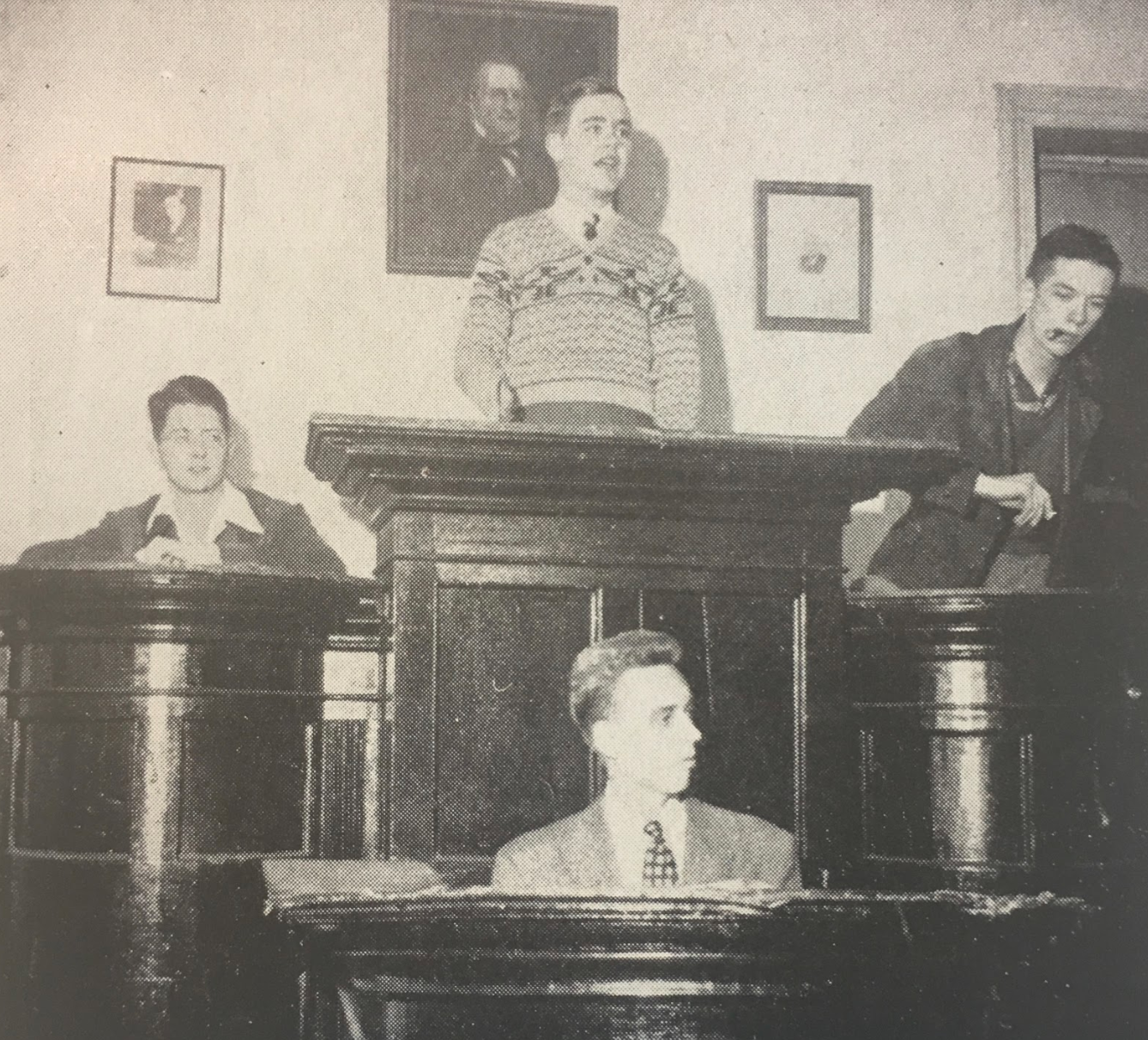

The Phi Kappa Literary Society is a student debate organization founded at the University of Georgia in 1820. It is the second oldest Greek-lettered collegiate society in North America as well as a part of the oldest collegiate rivalry in the United States. Since its beginning, Phi Kappa has served as a training forum for many public leaders and first families of Georgia and throughout the South for public speaking. Sixteen governors for the State of Georgia are among our former members.

Breaking Away

According to E. Merton Coulter’s College Life in the Old South, Joseph Henry Lumpkin (the future first Chief Justice of the Georgia Supreme Court) and several former members of the older rival society founded the Phi Kappa Society after they discovered that the older organization had grown lax and listless. However, little contemporary documentation corroborates this tradition and Coulter’s work has proven erroneous with many past and secrets of Phi Kappa.

What is known is that on February 12, 1820, the day after the celebrations of George Washington’s birth under the Julian calendar, William Crabbe, Homer V. Howard, Stern Simmons, John G. Rutherford, and John D. Watkins formally established the Phi Kappa Society with Howard serving as its first president. Later, the Society decided to move its anniversary celebrations to the Gregorian date of Washington’s birth (February 22). During his life, Joseph Henry Lumpkin did maintain a close relationship with the budding Society and was elected an honorary member during the Society’s inaugural year.

The Early Years

Though first looked upon by its rivals as a small secret clique, Phi Kappa quickly grew, reaching over 125 honorary and regular members in its first year. During the antebellum era, almost all college students joined either Phi Kappa or its rival Demosthenian. Both societies enjoyed great prosperity and eloquent oratory on a wide range of subjects from slavery to women’s education to the confinement of Napoleon on St. Helena. For the first three years of its existence, Phi Kappa could find no meeting place other than the garret of Parson Hope Hull’s old chapel. Then, in 1823, the Society moved into a wooden building it had erected on the University campus probably between the Chapel and New College.

Soon, however, the organization outgrew this structure causing future Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander Stephens to begin a subscription fund in 1832 to finance construction for a larger brick hall. With final donations of one thousand dollars from alumni members Howell Cobb, J.P.C. Whitehead, and Honorary member John Milledge, the brick Phi Kappa Hall was constructed in 1836 at a cost of $5000. On July 5, 1836, the final permanent home of the Phi Kappa Society was formally dedicated with jubilant celebration. At the first commencement in the new hall later that year, former United States Vice President and South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun presided at the special Phi Kappa meeting with University President Moses Waddel serving as the honorary First Vice President. Among the guests in attendance were Joseph Henry Lumpkin, Howell Cobb, his brother T.R.R. Cobb, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, and many other contemporary political leaders and celebrities.

Following Georgia’s secession from the Union and the coming armed conflict, university students began enlisting in droves. By 1863, only five members of Phi Kappa remained so the Society decided to disband and close the hall for the rest of the war. Following Lee’s surrender, Athens was soon occupied by Union troops. Sadly, Phi Kappa Hall was commandeered as a stable for the soldiers. The Hall was badly damaged and most of the Society’s property, including the valuable library, was looted or destroyed. Returning students repaired the Hall as best as they could, and on January 5, 1866, Phi Kappa Society meetings resumed. The instrumental hand in the refounding was future New South Orator and Atlanta Constitution Journalist Henry W. Grady. Later in life, Grady described his experiences in Phi Kappa as the best education he ever received.

Post-War

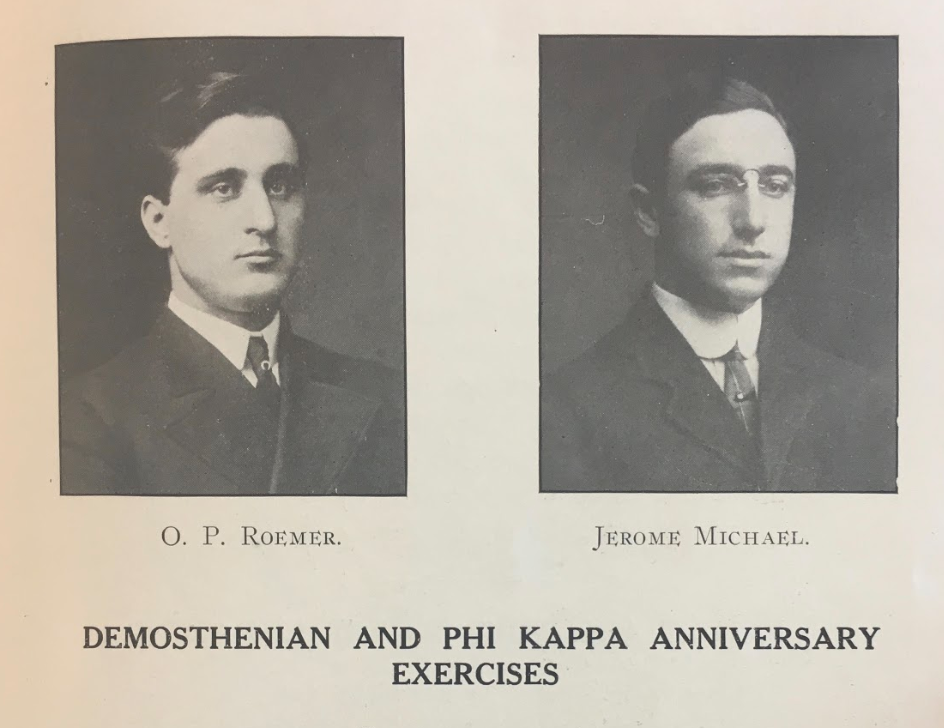

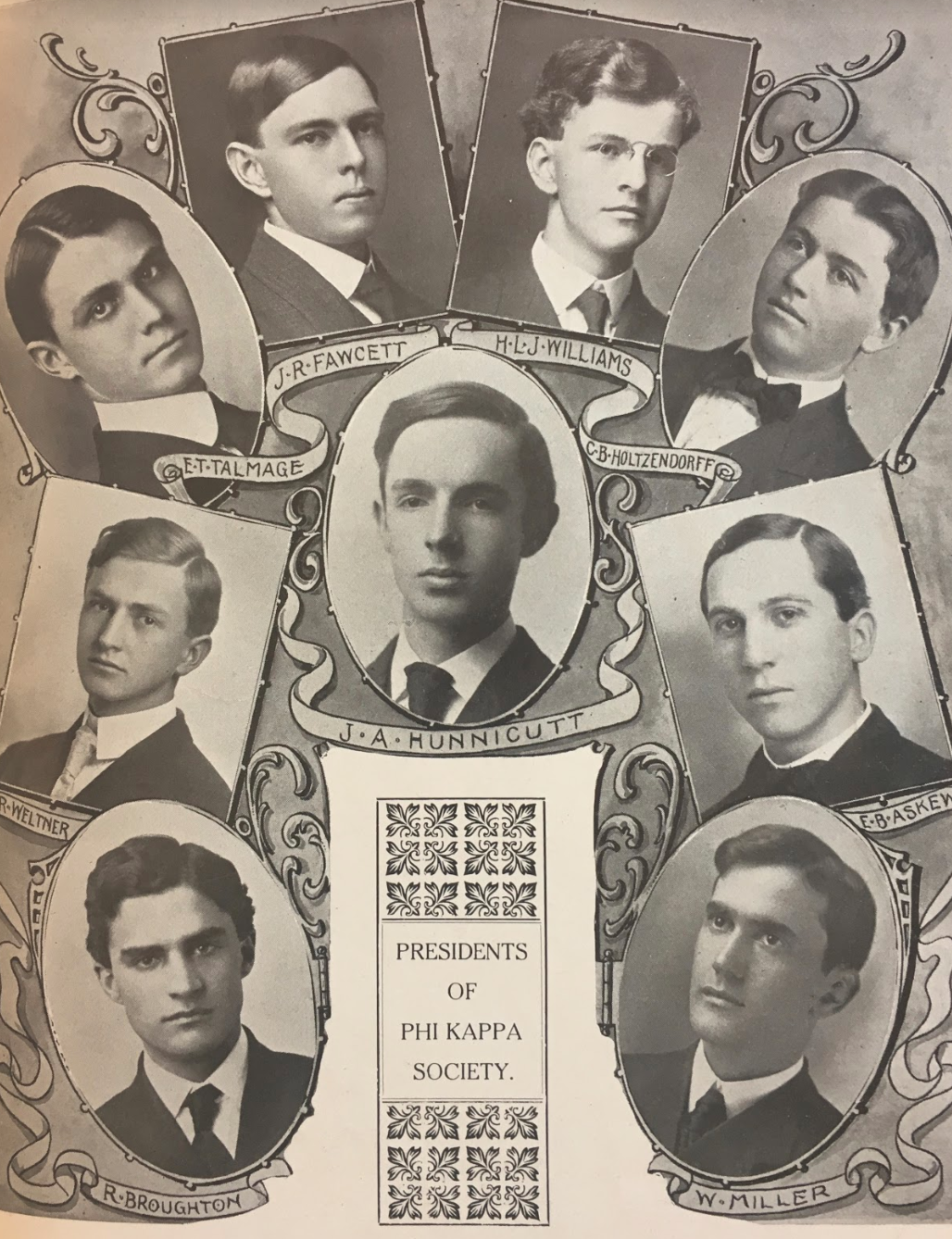

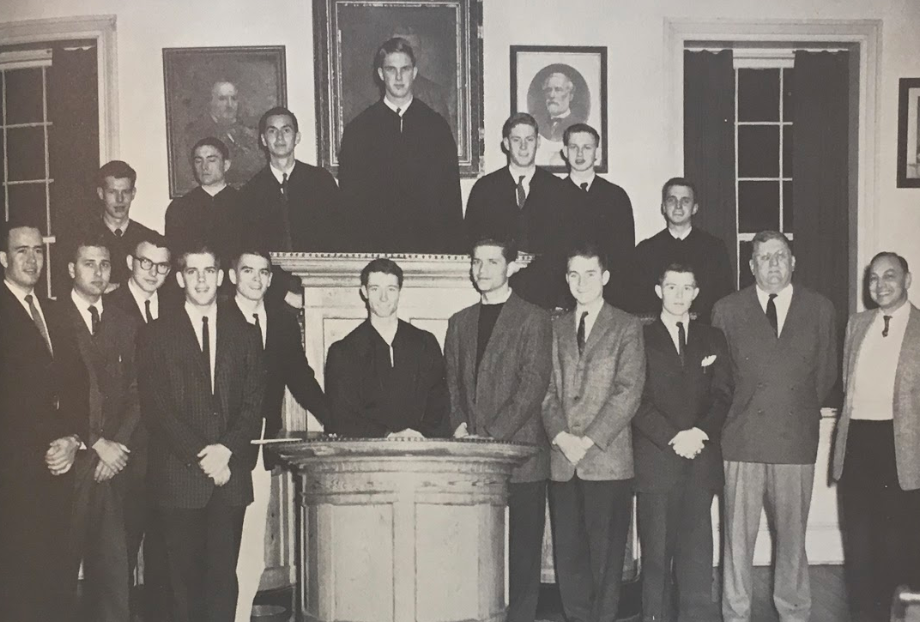

During Reconstruction and the latter half of the 19th century, Phi Kappa grew once more but had not fully recovered from the destruction of its property caused by the war. Also the rise of social fraternities, college athletics, and military programs gradually reshaped campus life and diverted energies away from literary societies. Then, finally, starting in the 1890s the Phi Kappa Society began to flourish once more. During this period Phi Kappa became a member of the Southern Oratorical Association and for several years sent a representative to participate in the Association’s annual meeting and oratorical contests. Also, from 1901 to 1916 UGA participated in 31 inter-collegiate contests and was victorious in 19. Phi Kappa furnished over 60 percent of the members for these collegiate debate teams. From 1931 through 1935 Georgia debate teams even participated in international debate contests against the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Trinity College of Ireland, and the University of Puerto Rico. For each University team, Phi Kappa supplied the leading members.

The Talmadge Incident

In 1935, the Society faced its greatest split up to that time as the Society was divided into pro and anti- Eugene Talmadge factions. Talmadge was the current governor of Georgia and a Phi Kappa alumnus. Possibly inspired by Huey P. Long’s involvement with Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, Governor Talmadge attempted to rule the University with a heavy hand, risking the loss of the University’s accreditation. Finally, the anti-Talmadge faction of Phi Kappa proposed a resolution calling for the impeachment of Talmadge. The resolution failed after a bitter debate and nine months later, Talmadge came to Athens to address an overflowing meeting of the Society in Phi Kappa Hall. At the end of his speech, he presented a large photograph of himself to the Society to hang on the wall alongside the portraits of other prominent alumni. For several years the two Phi Kappa factions debated over the fate of the photograph until Phi Kappa alumnus and future Georgia Governor Ernest Vandiver supposedly burned it on the front steps of Phi Kappa Hall. However, the fractious split eventually ended peacefully and another photograph of Talmadge now adorns a wall in Phi Kappa Hall.

“The instrumental hand in the refounding was future New South Orator and Atlanta Constitution Journalist Henry W. Grady. Later in life, Grady described his experiences in Phi Kappa as the best education he ever received.”

The Society After World War II

After the United States entered the Second World War, male enrollment at the University dropped rapidly. Finally, at the end of the 1944 Spring Quarter, the Society once again disbanded and the Hall closed its doors. During the War, many Phi Kappa alumni served bravely from the front lines to staff positions on the War Crimes Prosecutions. The most prominent war record of all alumni was that of Erle Cocke Jr. who survived a German execution squad and prisoner of war camp. With just a handful of men, he fought off a battalion of the enemy at a bridge and then, after the war, became the youngest President ever of the American Legion.

Following the war, a variety of new distractions caused oratory and debate to lose some of their former appeal. Nonetheless, Phi Kappa membership was maintained at an acceptable level, and the old-age rivalry with the “society across the way” continued. At this same time, the University faculty included several Phi Kappa alumni in positions of great influence including legendary Dean of Men William Tate, well-respected Dean of the Law School J. Alton Hosch, and University President Harmon Caldwell. These men would serve many years at the University and leave their permanent mark.

Protest and Change

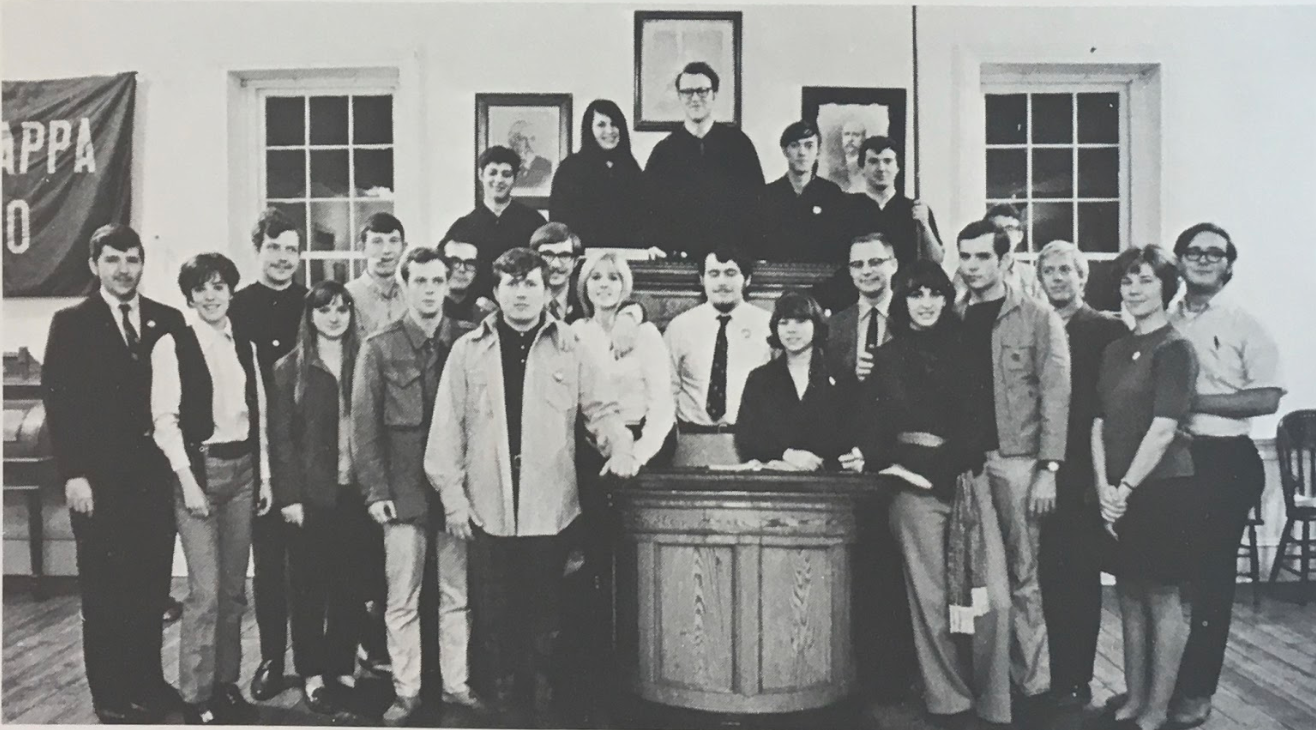

The decades of the 1960s and 1970s were periods of student protests, general unrest, and profound change on the college campuses throughout the United States. During this time, Phi Kappa focused on hot issues of the day with many programs featuring controversial speakers of the era including Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett to the Pacifists Committee for Non-Violent Action. One Phi Kappa special program caused an extremely heated discussion on campus. In October 1963 during the height of the Cold War, Phi Kappa attempted to sponsor a debate between a University economic professor and a representative of the Communist Party, USA. However, the Student Affairs Committee of the University refused to permit the debate and the University President O.C. Aderhold rebuked the Society for attempting to create what he called a “sideshow” and “riot” on campus. After 42 years, the Society renewed the controversy in 2005 by hosting a debate between University of Georgia economics professor Dwight Lee and Communist Party U.S.A. spokesman Wadi’h Halibi. However, this time the University welcomed the event and even co-sponsored it.

Unfortunately, Phi Kappa was not immune to the general turmoil many colleges faced during the 1960s. Phi Kappa soon found itself deeply divided into two political factions with extremely different views. All members were required to join either group. Any member wishing to speak had to secure the permission of the party leader rather than the President. These new procedures radically changed the structure of the Society and diminished the democratic, fraternal principles upon which the Society was founded and had flourished. Eventually, this discord caused an exodus of members and a lack of new recruits. In the end, the Society turned to the radical left and the Society lost its appeal to the overwhelming majority of students. The Society survived until finally disbanding in 1973.

The Refoundings

While the Alumni of Phi Kappa continued to thrive and prosper, several unsuccessful attempts were initiated to return the Society to campus. In January 1976, former Demosthenian President Bill Moorehead led a small group of disaffected members out of their hall and reestablished Phi Kappa. However, it soon died once more and attempts to revive it in 1979 and 1981 failed.

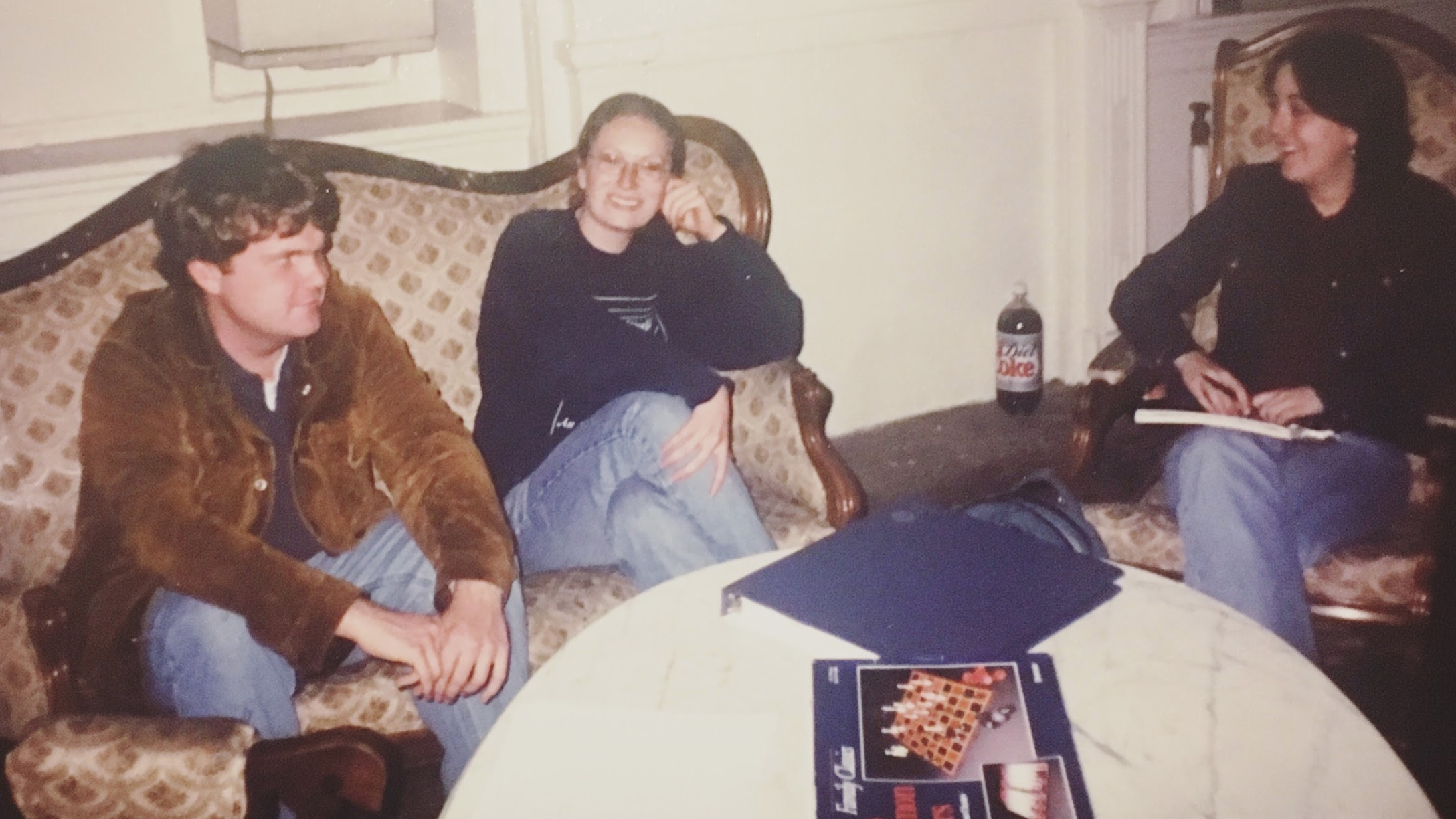

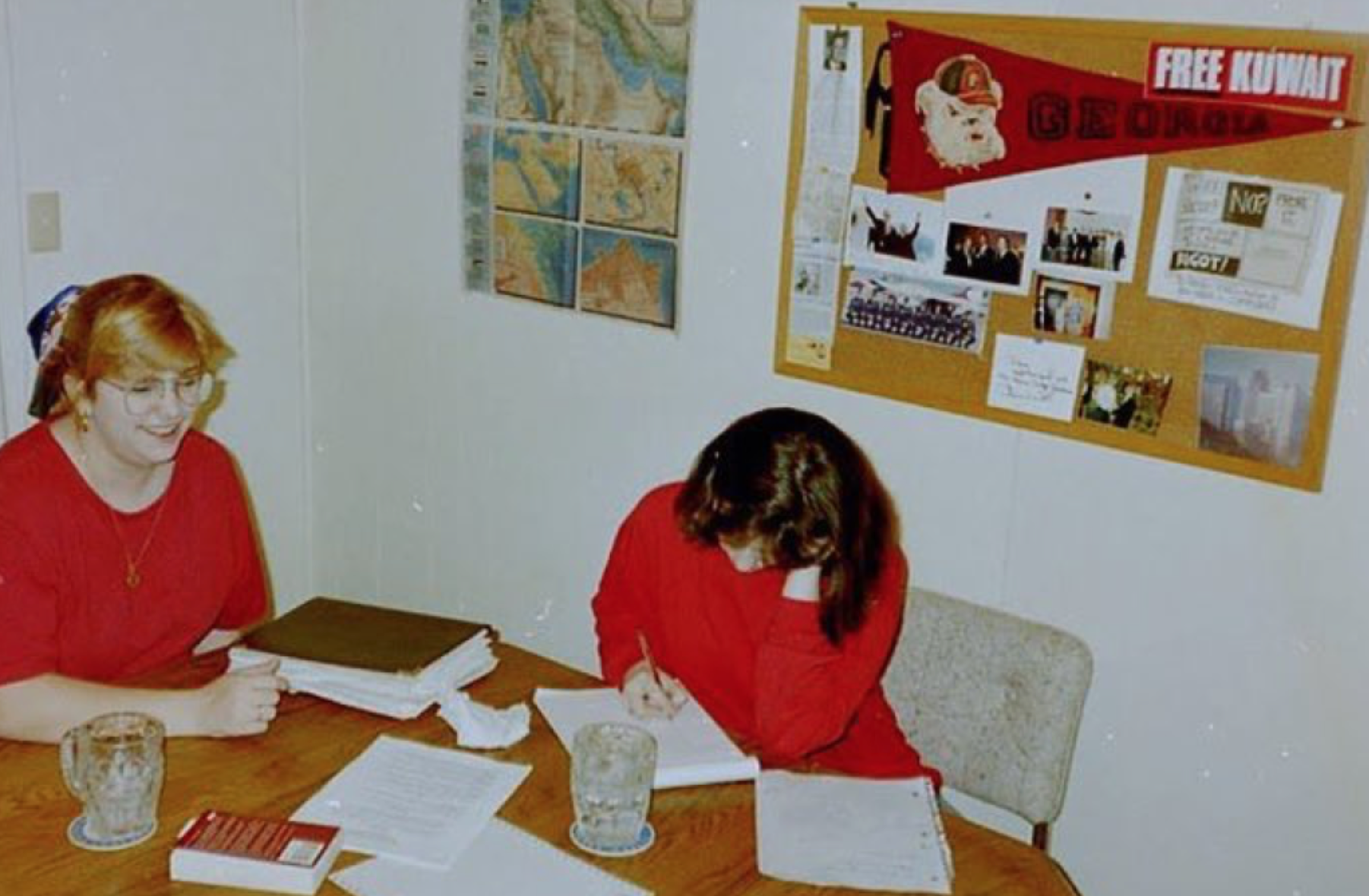

Not until 1991 was a successful refounding initiated by Thomas Peter Allen. After attending several meetings of the rival society, Allen was disappointed by what he saw and came to the same conclusion as Joseph Henry Lumpkin over one hundred and seventy years before- the University needed two debate societies. Before he could refound Phi Kappa, Allen was called to Washington to serve as an intern for Senator Sam Nunn. However, he passed his enthusiasm for Phi Kappa Society’s refounding to Stephanie Hendricks who served with Allen on the University’s Student Government Association. Along with a friend and sorority sister Elizabeth Schuchs, Hendricks researched the few available documents on Phi Kappa’s history and practices in the University archives.

Finally, at a closed meeting on January 31, 1991, Hendricks was inducted as the first President of the refounded Phi Kappa Society by former 1961 Society President E.H. Culpepper. After the ceremony, Hendricks proceeded to induct Elizabeth Schuchs, David Crabtree, Kristi Harris, Lauren Kelly, Doug Muse, Craig Senn, Margret Sullivan, Tony Waller, Michelle Watkins, Jennifer Whitaker and Marc White. Peter Allen was later inducted upon his return from Washington and was elected as the Society’s second President since the refounding. The first regular open meeting of the Society’s new era took place the night of February 14, 1991 in Phi Kappa Hall.

That night, the new Phi Kappans marched in a procession from their Hall across the quad to the Demosthenian Hall, up the stairs and into the rivals’ upper chamber. Phi Kappa First Vice President Doug Muse obtained the floor and announced Phi Kappa’s triumphant return to the campus of the University. This news set off a storm of emotion in the rival hall, and the Demosthenians decided to form a procession of their own and march across to Phi Kappa Hall. Upon their arrival at Phi Kappa Hall, the rivals issued a challenge to an inter-society debate which Phi Kappa accepted, and thus, the rivalry was reawakened.

Phi Kappa Renewed

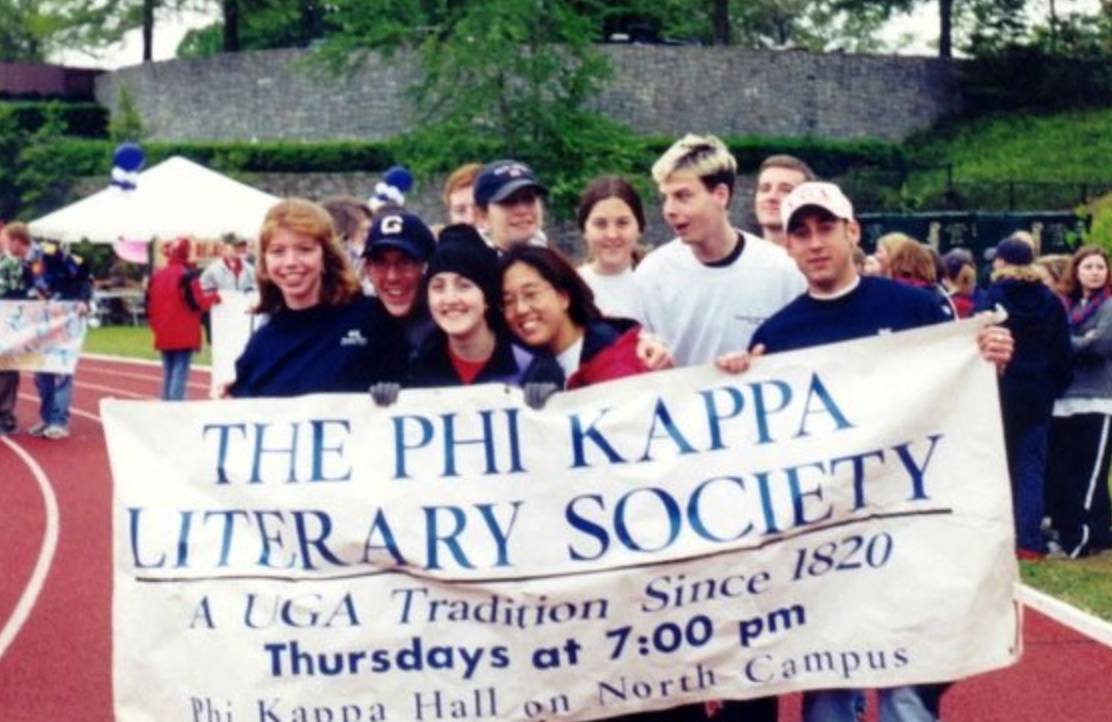

During the 1990s Phi Kappa once again prospered. Though not seen at first as the legitimate descendants of the Phi Kappa founders, the new members of Phi Kappa eventually gained acceptance by the University administration. Unfortunately, while Phi Kappa meets again in the upper chamber of Phi Kappa Hall, this meeting space is still not under the Society’s control like the meeting hall of the rival society which excises dominion over its entire building nor like the downstairs chamber of Phi Kappa Hall which is controlled by the Georgia Debate Union. Hopefully in the near future, the University will correct this mistake and give all its debate organizations equal treatment. Until then, the Society is diligently working to restore its rich traditions, customs, regalia, alumni communications, and history thanks to the efforts of such alumni as Lamar Merk, Kenny Hosley, Erin McClanahan, Michael Oberg, John Byrne, and Robert Hawk. The capstone of this effort came in 2005 when the hall received a long overdue renovation. The rededication ceremony featured Phi Kappa alumnus and then Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Norman S. Fletcher as guest speaker along with the University President Michael Adams as his honorary First Assistant.

The 199-year-old rivalry between the University’s two debate societies still remains intense with treaty negotiations still a point of contention. Currently, the two societies compete against one another in the Spring Semester Intersociety Debate. Each society fields a four-member team judged by three University faculty judges.

As Phi Kappa moves into the future, it constantly seeks to expand and improve, increasing its appeal to every student at the University who hates the thought of being average.